Identifying Art Fakes and Challenging Art Forgers with High Tech

As an art conservator, I am asked once a week (or more) to technically examine artwork in the hopes of “authenticating” it. Most of these requests come from people that have already been through a lot of discussions with art experts or institutions that they consider were not “helpful.” In fact, most people hit a lot of dead ends from people not taking them seriously. This article will explain some of that dilemma. I mean if your life, as a mild mannered scholar, were threatened would you be available to the public?

Separating originals from fakes has become a risky business but new tools help spot the cheats. But first, lets discuss the questions you should ask. Assuming you are reading this article because you have questions about the process, the first step is to get a clear picture of the nefarious world of art authentication and fakes. Second, is to clarify, what you actually want to achieve from the process. Let’s illustrate the problem with getting your ideas clear about what you want.

“Is it authentic?” isn’t really the right question to ask. Here are a few more exact questions you may want to asking instead.. Is the artwork from the period it should be? Is the signature added or original. Was the signature added after the artwork was dry or mixed into the paint? Is the writing on the back original? Are the labels original or added (I have seen many fake labels… or taken off of other paintings)? Are there restorations? How many previous restorations? When was the last restoration? There are so many unethical restorers and art dealers “out there” working together that it could be said that the majority (not all) are dishonest. What was the reputation of the dealer(s) that handled your artwork? Is it worth the effort and expense to pay for research and analysis to authenticate?

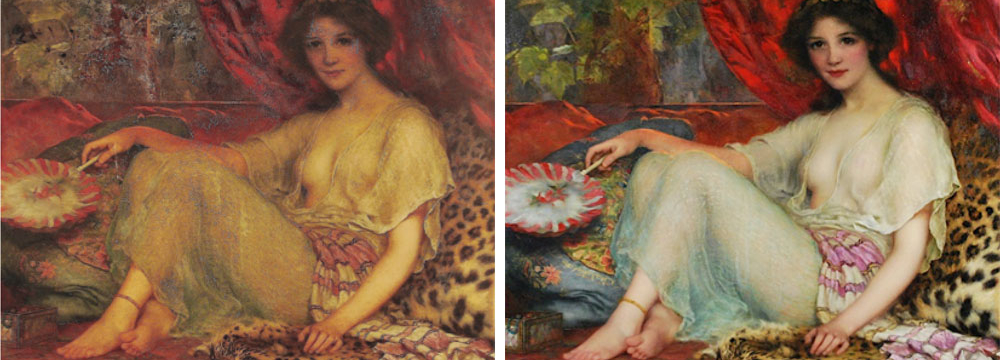

This is a BBC TV program on finding lost treasures through authentication, going now for several seasons and a great success. Note the portrait of the woman on the floor. This painting was in our lab for cleaning and research. See the link to the short video of the interesting story and the very peculiar way it was authenticated later in this article.

What does it cost? You may pay a couple of hundred $ just to quickly have an expert look at it an offer some guidance. And in this episode of Fake or a Fortune, they gallery owner spend over $30,000.00 of the process: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01n62dw There are lots of variables, options, processes, types of analysis… and analysis or technical evaluation is not the end all for many experts.

The research of the art and its history is a very exciting part of the process of authentication. Here’s a quick interview with a world famous harpsichord maker and restorer who also collects paintings: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7ltm5sJTChc

The world art market is flooded with fakes and forgeries. There are a lot of emotions and money wrapped up in this world, as you can imagine. Art experts have faced legal action and even death threats for refusing to authenticate works as original.

Years of trying to figure out a good way to get the job done, often under extreme mounting pressure, experts are responding by establishing an organization to give them confidence to express opinions without fear of retaliation.

The ICRA (International Catalogue Raisonné Association) is a not-for-profit group that will support the production of definitive inventories of an artist’s accepted artworks. At the Royal Academy of Arts in London it was organized last June 2019,with the aim of helping to limit the flow of fakes, partly by giving authenticators access to discounted specialist legal advice.

Says ICRA founder Pierre Valentin, head of the art and cultural property practice at law firm Constantine Cannon in London “At a time when authenticity committees are closing down, and experts are being threatened and becoming concerned about expressing an opinion for fear of retaliation, it is really important that scholars and experts have a place where they can feel free to talk, discuss and share.”.

The Andy Warhol Foundation disbanded its authentication board after a 2007 lawsuit over its refusal to authenticate a silkscreen print. The foundation does not deny reports its legal costs ran to millions of dollars, and says the experience prompted its decision to close the board and spend its money on “artists, not lawyers”. A silkscreen print that the Andy Warhol Foundation refused to authenticate The estates of several other 20th-century American artists, including Jackson Pollock, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring and Roy Lichtenstein, have also closed their authentication services, to avoid the legal tugs-of-war involved in being both arbiters of authenticity and owners of works — where, for example, decisions might affect the value of works they themselves hold. “It is becoming increasingly obvious that liability claims are regularly brought against the experts or connoisseurs,” says Marc Restellini, a Paris-based art historian whose catalogue raisonné of early-20th-century master Amedeo Modigliani will be published next year. “The fact that they have become a threat and a weapon to try to intimidate them is obvious and unacceptable.” Some art experts report even worse forms of intimidation. “I’ve had my life threatened because I didn’t do what somebody wanted,” says Richard Polsky, a California-based authenticator who specializes in valuable American artists whose estates have stopped their authentication services.

As an example of the difficulties involved in authentication. Former forger Ken Perenyi says at least 2,000 of his forgeries of sporting and marine pictures by 18th- and 19th-century British and American artists are “certainly out there”. His advice is “caveat emptor.” This flippant advice should guarantee him 30 years in prison, in my oinion.

In New York, the well know, even famous IFAR (International Foundation for Art Research) has offered an art authentication research service since 1969. One fake Jackson Pollock came with letters and photographs purporting to show the painting had been hidden for 50 years in Fidel Castro’s Cuba. IFAR concluded the evidence was part of an “outrageous” scam. In a research paper, Lisa Duffy-Zeballos, IFAR art research director, noted that “the painting’s style had no relation to authentic works by Pollock”. Crucially, IFAR established that accompanying photographs had been doctored. Two showed Pollock, “or someone who looked like him”, in a loft-style studio, with the IFAR painting on display. In the background in one photo was another painting that strongly resembled works by another American painter, Franz Kline. Research revealed that the photograph had been digitally altered from a 1954 Life magazine photo of Kline. Sharon Flescher, IFAR’s executive director, says the organization was asked to authenticate Pollocks by the Pollock-Krasner Foundation after it was sued three times, albeit unsuccessfully.

Michael Daley, director of ArtWatch UK, an art conservation campaign group, “There is an acute problem developing, in that fewer and fewer scholars seem to be trained in the vital skill of what might be termed ‘forensic looking’,” he warns. He adds that, in any case, national museum curators are increasingly forbidden to pronounce on artworks. “Their lawyers are telling them not to risk it.” Fewer and fewer scholars seem to be trained in the vital skill of what might be termed ‘forensic looking’ Michael Daley, director of ArtWatch UK Polsky, the California-based authenticator, says he has come to realize how pervasive forgeries and scams are in the art market. “The reason I work with Lichtenstein, Warhol, Basquiat, Haring and Pollock is because they have the most problems with fakes,” he says. “And collectors have nowhere to go since all of their authentication boards went out of business back in 2012. “When you have a business that is unregulated — this is the key to the whole thing — people make up the rules as they go along. It is like someone waking up in the morning and says, ‘Hey, I just read a book on medicine: let’s open an office and become a physician’.”

Art authentication is not an exact science, but scientific methods are becoming so advanced “that it becomes more and more difficult to produce forgeries”.

In 2016, Sotheby’s acquired Orion Analytical, a conservation science lab, becoming the first auctioneer to have an in-house service. It followed the discovery that in 2011 it had sold a fake Frans Hals, the Dutch master, for £8.5m. Pigment tests showed it could not have been painted in the 17th century. Sotheby’s refunded the buyer. “With the technology available to the forensic laboratories today, the chances of a fake standing up to the challenge of such analysis is almost zero,” says former forger Perenyi, who operated in the 1980s and 1990s. But he adds: “Anyone who thinks such obstacles will rid the market of fake paintings will be in for a disappointment. Art forgers are always thinking a few steps ahead.

A fake Edgar Payne “embellished” with an $8,000.00 hand carved, water gilt frame to “sell the sizzle.”

Would all this hoopla occur when someone asks me if I will authenticate a painting by their (only locally known) grandmother? I actually had this request?!?! No, of course I doubt my life would be threatened. How about for inspecting a signature of an Edgar Payne to see if its authentic? Although I’ve done this dozens of times, not yet. What kind of fooey would hit the fan when I discover 4 fake signatures on a $35 painting from a thrift store? Probably no much fall out.

There are many aspects, turns and types of authentication of art and antiques. Asking the correct questions is the place to begin. Start with the least expensive methods of analysis and look for “red flags.” If you find titanium white on your priceless Russian Renaissance Icon after $300 of analytical work, you are done.

Recommended fun on this subject: On Netflix see Fakes or a Fortune.

For more info call Art Conservators

Scott M. Haskins, Virginia Panizzon

805 564 3438 faclofficemanager@gmail.com

Fine Art Conservation Laboratories, Scott M. Haskins, Art Authentication, Art Conservation, Art Restoration, painting conservation, painting restoration, Virginia Panizzon